Table of Contents

Is it acceptable to replace my boat engine’s steel bolts with stainless steel bolts?

At first glance, it may seem like an obvious answer. Boats are used in water. Water, especially saltwater, corrodes steel. Stainless steel is corrosion resistant so therefore, it would be better to replace the bolts in my engine block with stainless steel.

Am I a genius or what?

Let me stop you right there. You just might be a genius but unfortunately, it is not that simple. There are a lot of different factors in play.

Is Stainless Weaker?

Not all steels are made equal. And unfortunately, commonly available stainless steel such a 304 (A2) and 316 are normally on the weaker side when it comes to tensile strength.

High tensile steel is so-called because they have additional alloying ingredients that improve their tensile strength. Some of the alloying materials include chromium, molybdenum, silicon, manganese, nickel, and vanadium. High tensile steel bolts can withstand high tensile forces such as that which the engine block bolts will be facing during operation.

Failure of the bolts that hold your engine together during operation, as well as being a major safety hazard, may well result in you having to purchase a new engine.

While there are a few stainless steel bolts that are able to match the tensile strength of high tensile steel bolts, they are harder to find and are usually more expensive. In the UK it's easy to fall into the trap of popping to Toolstation or Screwfix to buy stainless steel fasteners. They're cheap, cheaper than ever in fact, but they're not always suitable for the application and we'll tell you why.

Understanding Tensile Strength

Ultimate tensile strength otherwise known as UTS is the maximum amount load/stress that any given material can withstand whilst it's bent or pulled in any given direction before fracturing/ breaking.

Don't been fooled into thinking tensile strength is limited to fasteners. In fact, it's used throughout a boat as a method of measurement. Even the sealants used around your window frames have been rigorously tested. Much like steel, sealants have an elongation limit which is hit before breaking.

In order to understand it in a basic sense let's compare an example. Just remember stainless steel comes in many different grades, each having different properties that make them suited for different applications.

304 Stainless Steel

| Physical Properties | Metric | English |

|---|---|---|

| Tensile Strength, Ultimate | 505 MPa | 73,200 psi |

| Tensile Strength, Yield | 215 MPa | 31,200 psi |

| Elongation at Break | 70 % | 70 % |

Grade 8 Steel Bolts

| Physical Properties | Metric | English |

|---|---|---|

| Tensile Strength, Ultimate | 1034 MPa | 150,000 psi |

| Tensile Strength, Yield | 896 MPa | 130,000 psi |

A Summary

Notice the yield strength is higher in 304 stainless steel. Then let's think about what that means.

"Yield Strength is the stress a material can withstand without permanent deformation or a point at which it will no longer return to its original dimensions (by 0.2% in length). Whereas, Tensile Strength is the maximum stress that a material can withstand while being stretched or pulled before failing or breaking."

So now we've found stainless steel that has a high yield, why not find one that has a high tensile strength? Sure.

Stainless Steel 440

| Ultimate Tensile Strength | 1750 MPa | 254,000 psi |

| Tensile Yield Strength | 1230 MPa | 186,000 psi |

So perhaps you're thinking Stainless Steel 440 is the wonder metal and why aren't we all using it?

It all comes back to availability and costs. The average person in a hardware store is probably buying stainless steel as "they heard it don't rust". They'll be using it for a garden bench or possibly an outdoor structure. It only needs to withstand, auntie Lills 350 pound ass. Whereas your engine bolts may need to take 8,000 to 10,000 lbs of pressure to seal a gasket.

So now you understand that all stainless steel isn't the same and as we previously stated there are more factors at play than strength.

High Tensile Steel & Grading

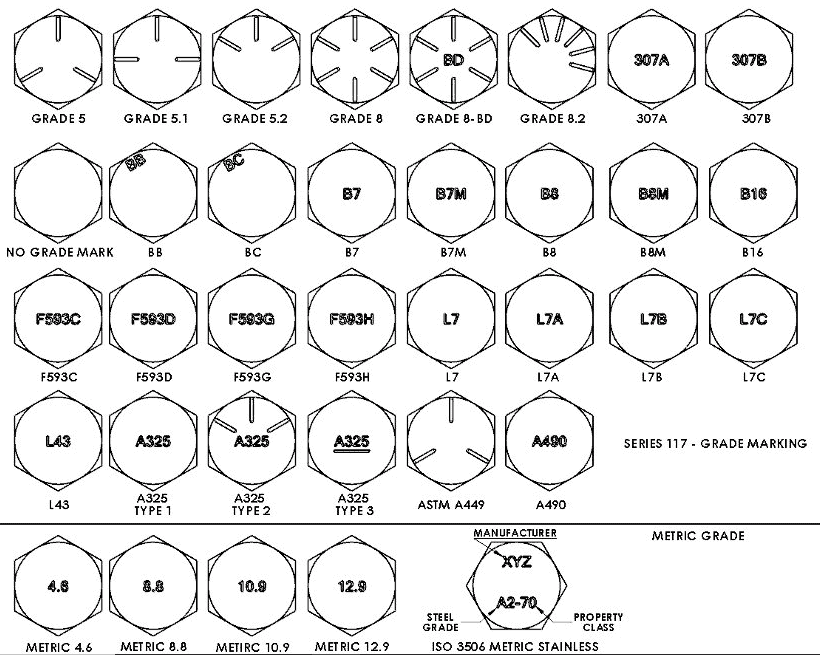

If you're new to mechanics and engineering you might not realise that the majority of bolts are graded and often marked. Hex bolts, often have a marking on the top of the head. ISO strength rating ratings may also be listed. Some of the more common markings are 10.9, 8.8, and 5.8. The number before the decimal point is the ultimate tensile strength in MPa divided by 100. these can be linked to a grade. This information is key, it can give you the tensile strength the resistant, the chemical makeup. Bolts without marking may not be graded and of poor quality. Below is a chart from the Cifbolts technical library containing some of them common gradings you might stumble across.

Can’t see a marking on your bolt?

In the majority of cases, you're restoring an engine because it's broken or dated. This means its likely that your bolts might not have their original markings due to corrosion, rust or wear.

Another thing to consider is that your engine, maybe older than your nan's bone china. The history of threads goes back as far as 400 BC but fortunately for us the first gasoline-powered engine wasn't developed until 1859. Notably, It wasn't until World war 2 that bolts were standardised worldwide in an effort to unify threads. Imagine going to bolt in your turret gun only to find out its got a different thread, Doh! Will you stop waffling on. Sorry!

So in short, you need to consult your workshop manual if you can't see any markings. If that fails there are plenty of technical groups out there; where someone will have worked on that particular engine.

A Useful Tip

If you can't see marking on your bolt heads try use a brass dipped wire brush to reveal them. Steel brushes work but they have a tendency to leave microscopic particles of steel on a surface. The brass dipping helps prevent this; to a degree.

WHAT ABOUT CORROSION?

Here’s another thing to consider.

If you have an aluminium engine block and use stainless steel bolts, your engine could be at risk of bimetallic corrosion. The aluminum will be the anode and the stainless steel bolt the cathode. This will result in corrosion between the two materials especially in a marine environment. It is usual for pitting to occur in the aluminum threading. In extreme cases, the stainless steel bolt can seize in the engine block and the head of the bolt break off when too much force is applied to remove the bolt. This is a very inconvenient occurrence as anyone who’s experienced this can attest to.

To reduce the likelihood of this, ensure that you coat the threading of your bolt with anti-seize before installing them. It acts as both anti-seize as well as insulation between the anode and cathode.

High tensile steel bolts, on the other hand, are not at risk of bimetallic corrosion with your engine block. A well lubricated and maintained engine will keep your high tensile bolts as good as new. You will also be able to rest assured that the bolts will not break due to tension forces from your engine’s operation.

With the exception of stretch bolts, the recommended and foolproof way to go is to reuse the original bolts that came in the engine. If a bolt is damaged and needs replacement, try your best to replace it with one that has the same properties as the original. The manufacturers usually know what they are doing but we get you! Sometimes paying £30 for a "Genuine Volvo Penta" bolt can seem a bit ridiculous.

Don’t hesitate to get professional advice if you are unsure about making modifications or even during routine overhauling. It just might save you a few bucks.

Confused about the difference between corrosion and rust? Check out our article here.

Consider The Underhead Configuration

By Tom Salveta

The underhead configuration being the bearing surface, flat to concave angle and body to head radius are extremely critical in high tensile fatigue prone applications like cylinder head bolts. If you modify the bearing surface you are going to totally change the torque tension ratio and potentially dramatically over or undershoot the engineered clamp load.

A big part of the friction comes from the underhead surface. When you change that surface area, or change the angle of the surface It's not very obvious, but the underhead surface is usually not perfectly flat especially on cylinder head bolts.

Still, stuck? Let me jump back; what is a bolt? It's a device for holding two pieces together by attention Tension It acts like a big spring Unfortunately we don't often take direct measurements of that tension. Instead infer the amount of tension based on an applied torque value because it's easy to measure. Measuring tension directly is very expensive and very finicky Torque is a resistance to a force, AKA friction. So what we are relying on is a uniform and repeatable amount of friction on every joint and from every fastener.

I don't mean to say every fastener on a boat is painstakingly designed, but for critical applications like cylinder head bolts, engine mounts, rudder stock or chainplates it is most likely that someone sat down and tested the torque values, therefore it's never as simple as using any old bolt in your restoration.

Article by Alshane Brown

Edits & Contributions by Louis Derry & Tom Selveta

Additional Sources

Bolt Chart https://omnexus.specialchem.com/

A history of threads https://www.nord-lock.com/insights/knowledge/2017/the-history-of-the-bolt/

I missed where you posted where the bolts are to be used on the “engine”. If you are talking about engine mounts – sure, why not? If you are talking about key bolts like head bolts, or bearing bolts – resist the urge. The engineering involved in these engines – especially Diesel engines – requires bolts that can take the extremes in the application. Stainless steel – indeed – is weaker than regular steel bolts and much weaker than the hardened steel bolts used in those key locations like head bolts. No way should you mess with that. Besides there isn’t much corrosion going on in those oil bathed locations

I hear you Daniel, I’ve expanded on the article now, I agree that it was perhaps missing some key elements. Thank you for your feedback.

If the yield strength of 304 SS is 31,200 psi and the yield strength of grade 8 bolts is 150,000 psi why is 304 stronger than normal steel?

I hate to say you might have missed a major point, speaking as a restoration engineer, while stainless steel is obviously good, it will induce galvanic corrosion if butted up against normal carbon steel. I’m basing this off by your mention of bolts but not other structural members, assuming that the other members are steel. If on the other hand, you tell me that the other members are fiberglass or CFRP then the stainless bolts and their associated washers and nuts would work in those instances.